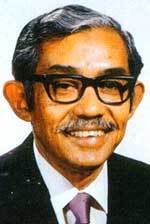

Tun Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman was the Deputy Prime Minister when Tun Razak was the PM. He died as acting Prime Minister on Aug 2, 1973.

Tun Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman was the Deputy Prime Minister when Tun Razak was the PM. He died as acting Prime Minister on Aug 2, 1973.A soon-to-be-released biography of the man, The Reluctant Politician: Tun Dr Ismail and His Time, reveals just how critically important he was to the country.

It is the first authoritative biography of one of Malaysia’s most respected founding fathers.

Written by Singapore’s Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) Fellow Dr Ooi Kee Beng, the long-awaited work is based on Dr Ismail’s private papers and in-depth interviews with friends, colleagues and subordinates, including Prime Minister Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. A key source material is Dr Ismail’s own unfinished autobiography — an unpublished manuscript that was among the papers placed under the care of his son, Tawfik.

Read here full article

"...Dr Ismail’s failed plea to MCA president Tun Tan Siew Sin NOT to "pull out" the MCA from the Alliance Government in 1969. Dr Ismail believed it played into the hands of racial extremists and led to the May 13 clashes.

...Dr Ismail’s recollection of a missed opportunity to dissolve the parties that made up the ruling Alliance and form a single multi-racial party. It was an idea he apparently discussed with Tan in the late 1950s.

... Tunku Abdul Rahman wanted Dr Mahathir Mohamad expelled from Umno after Dr Mahathir’s criticism of the Tunku.

Tun Dr. Ismail's stern, no-nonsense approach inspired respect among friends and foe alike. It struck outright fear in the hearts of Umno’s legendary firebrands, including Tan Sri Syed Jaafar Albar.

..... his unflinching faith in multi-racialism, moderation and fair play, as well as his intolerance of bigotry and corruption.

His role to stabilise and heal the nation earned him a reputation as the man who brought Malaysia back from the brink.

The story climaxes in his final days as a leader struggling with his failing health and a terrible secret — that Tun Abdul Razak was terminally ill.

The book recounts how Tun Abdul Razak, upon returning to the country from a working trip after Dr Ismail’s death, exclaimed in despair: "Who am I to trust now?"

Excerpts from The Reluctant Politician: Tun Dr Ismail and His Time by Ooi Kee Beng (2006). Read here for more

On Tun Abdul Razak

Tun Razak's main task as Deputy Prime Minister was to consolidate his position among the Malays, leaving the Tunku to look after the non-Malays.

His political image during the period when he was deputy was that of a Malay leader, viewed with suspicion by some non-Malays and regarded as anti-Chinese, by others.

However, since becoming Prime Minister he has managed to change his image to that of a leader of a multi racial country.

The Malays accepted this new image and regarded it as a political strategy rather than a true change of personality and views; the Chinese sighed with relief at this metamorphosis.

The first act of Tun Razak as Prime Minister was to convene a meeting of divisional heads of Umno. At this meeting, he announced his future policy and also named me as his deputy.

This was the first time that my worth to the nation was admitted by a Prime Minister. The Tunku never acknowledged my worth publicly, although to a few chosen friends he admitted that I was indispensable to the nation.

And he quoted especially my handling of the May 13 affair and my defence of him in the period following this incident, when he was subjected to attacks of such obscenity by the Malays that one felt ashamed of them as a race.

By calling a meeting of Umno and not the Alliance to make his first public stand, Tun Razak was serving notice to the Alliance and the country as a whole, that from then onwards the government of the country was in Umno’s hands and the others were only supporters.

It was a bold move and was unchallenged. It also marked the emergence of a new personality.

This general acceptance of his new political image coupled with the general improvement of his health.....has given him self-confidence and enabled him to shed off those fears and worries that he lived with as Tunku’s deputy.

Tun Razak is an able administrator and a shrewd politician. As an administrator, he manages to get things done with little fuss and argument.

He has laid down the infrastructure of Malay participation in the economic life of Malaysia and is now busy prodding them to take advantage of the facilities being made available to them.

As a politician, he is shrewd, cautious and has the ability to handle people.

His main disability is his lack of charisma.

On the Future of Malaysia

The three policies, which will determine the future of Malaysia are:

1. The implementation of Malay participation in the commercial and industrial fields;

2. The need to maintain and, if possible, to decrease the rate of unemployment;

3. The neutralisation of South-East Asia.

The implementation of Malay participation in commerce and industry

I foresaw that if we were to get anywhere near to solving the problem, we must paint a clear picture of what was going to be done for the Malays without unduly frightening the non-Malays.

I suggested that there must be a target to aim at and that this target must be reasonable and what was more important, capable of being implemented.

I said that we should aim at a target period of 20 years within which 30 per cent of Malays would participate in commerce and industry and that it should be implemented in the context of a growing economy.

This proposal was unanimously accepted. At the time of writing, the implementation of this policy has been going on for almost two years.

Although the policy is clear if it is seen in its entirety, in the course of implementation, various sectors of our society chose to see it only from a sectional angle.

It is obvious that participation must mainly depend on new activities in commerce and industry.

This should NOT be difficult to achieve in a developing country like Malaysia, because new industries and new trading opportunities are constantly being established and offered.

Instead of trying to identify and promote new industries for Malays to participate in government and government-sponsored agencies, officials use all sorts of strategy to inject Malays into existing established industries and businesses.

The Chinese, on the other hand, instead of accepting the fact that new fields in industries and commerce must benefit the Malays, use all commercial and business tactics to prevent this from taking place.

The implementation is further distrusted by the Malays when they refuse to see the picture of implementation as a whole and rather choose to see details of implementation in isolation.

The present Malay interest in capital accumulation when compared to that possessed by non-Malays is one example. They argue that the present rate of government injection of capital into Malay commercial enterprises and trading institutions is so slow that in 20 years Malay capital accumulation will not only not achieve the target but the gap will widen. They forget or choose to forget the fact that capital accumulation can be achieved NOT only by means of injection of fresh capital but rather by the multiplication of existing capital through normal business activities.

The Chinese, for example, achieved their present capital largely by business activities. Some of the big Chinese businesses achieve their success by this method.

The Malays want the government to restrict the business activities of the non-Malays while the Malays reach parity with them.

If this philosophy is accepted, then the whole concept of Malay participation in a growing economy is replaced by a policy of Malay participation in a standstill economy.

This is neither politically possible nor is it practical from the government point of view.

Injection of capital into the Malay sector can only be done if government taxes keep on increasing as the economy expands.

Another problem that is cause for concern is the manner by which the Malays want the government to improve the quality of Malay manpower.

The government policy of doing this is, first of all, in the existing seats of learning — where there are more qualified Malays seeking to enter than there are places for them — to reserve a quota for Malays.

This is a reasonable way because all qualified Malays will be accommodated, and if there are surplus places they should be given to non-Malays. It is true that by this policy, the time taken to bridge the gap will be slower than if the government were to deny surplus places to non-Malays. But this is a practical and just way of doing things in a multi-racial society like Malaysia.

On Tunku Abdul Rahman

The Tunku’s greatest assets was that he managed to be himself under all circumstances no matter where he was, be it the palace or the kampong, in high or low society, whether among the rich or the poor.

This quality of his is still with him. People thus began to know him as a person with faults as well as virtues.

His blunders — of which there were many — used to shock people at first, but as time went on, people got used to him and they forgave him because he was great enough to admit his faults in public and make his apologies in public.

These lapses of his — the blunders and the mistakes — used to disarm many people who thought of him as a well-meaning leader with little brains.

I remember people saying that Malcolm MacDonald (the United Kingdom Commissioner-General for Southeast Asia, 1948-1955) once thought of the Tunku as an unstable leader.

However, beneath the superficiality, the unimpressiveness, lies a subtle brain which approaches political problems differently from others, and whose answer to those problems appears so naive that at first, many people would laugh but which once acted upon proved effective and practical (Drifting c6).

He was steadfast in his desire to talk with (the Communists) and could not be dissuaded; so the next best thing was to ensure that when the meeting took place, the Tunku was well briefed and his security not endangered.

Tunku himself was adamant that a safe passage be guaranteed for Chin Peng and his aides.

It says much for the trust that Chin Peng had in the Tunku that he accepted the invitation to meet the Tunku, knowing full well that he was throwing himself at the mercy of the Tunku and the British (Drifting c11).

The UMNO-MCA Alliance

Dr Ismail recollected that a strong team of MCA intellectuals held a debate with Umno on critical issues.

Most of these men were new, and "while they sensed that there was trust and confidence which had been built in the Alliance... they had not themselves experienced it and their approach at the meetings was, at first, critical".

Dr Ismail felt that all parties soon came to agree that whatever the problem was, the Alliance format would provide an appropriate answer: " As I saw this spirit emerge and expand during the rest of the conference, I was convinced that whatever happened in the future, this spirit of the Alliance would triumph over all obstacles. As a result of this new consciousness, the solution to many communal problems became possible" (Drifting c12).

The major dilemmas that were being faced were those of citizenship, the national language and the special position of the Malays.

The following text by Dr Ismail reveals his understanding of Malaya’s post-colonial situation (Drifting c12):Citizenship

Under colonial rule, there was a cumulative increase in the population of immigrant races, especially those of Chinese origin and to a lesser extent the Indians, the latter brought in mainly to work in the rubber estates owned by the British.

NO attempt was made to make these immigrants loyal citizens of Malaya.

The British were content to see that so long as they obey the laws of the country, they could come and leave as they please.

As a result of this policy, when more and more of them settled in Malaya, the result was an increasing number of aliens in the country who, on the whole, were richer and more vigorous than the Malays.

When the Malays seized political power after the Second World War, their main defence against their more virile and richer neighbours was to deny them the right of citizenship.

The Language Issue

As a result of colonial rule, the only language that could guarantee a livelihood for those entering the government service was English.

Otherwise the various races were left to themselves with regard to education.

There was a feeble attempt to give the Malays an education in their own language but as this ceased at the primary level and was implemented in a half-hearted manner, it gave no benefit to the Malays.

The Chinese were left to themselves and to run their own schools, which were financed through levies that they imposed on themselves, on their rubber production and their businesses. Their education was orientated towards China.

As a result, only the English-educated in the multi-racial population of Malaya enjoyed a common language.

The leaders of the Alliance concluded that in an independent Malaya, there should be one language to unify the various races into one nation.

The obvious choice was Malay. It was imperative that if the Chinese — the real political problem since the other races were not dominant — were to be persuaded into accepting Malay as the national language they should be granted citizenship as a quid pro quo.

This was the real basis of the agreement between the three partners, particularly between the Malay and the Chinese.

The Special Position of the Malays

This proved a less intractable problem because the leaders of the Alliance realised the practical necessity of giving the Malays a handicap if they were to compete on equal terms with the other races.

The only point of controversy was the duration of the ‘special position’ — should there be a time limit or should it be permanent?

I made a suggestion which was accepted, that the question be left to the Malays themselves because I felt that as more and more Malays became educated and gained self-confidence, they themselves would do away with this ‘special position’.

In itself, this ‘special position’ is a slur on the ability of the Malays and only to be tolerated because it is necessary as a temporary measure to ensure their survival in the modern competitive world: a world to which only those in the urban areas had been exposed.

This analysis provides insight into how Dr Ismail perceived the Malaysian situation.

What is striking is Dr Ismail’s belief that the Malays would do the right thing in the long run, as well as his faith in the Alliance as a model of government capable of meeting these challenges taken as a whole.

No comments:

Post a Comment